Logarithms Are Clocks

4/14/2023 • Rohan Mehta | Logarithms, Mathematics

I've always had a problem with logarithms. Not that I don't like them – in fact, I love them! There are so many ways to turn a logarithm on its head, to twist it inside out or upside down, that doing algebra with them can't help but be fun. But as much as I enjoy applying logarithm rules, I hate remembering them.

So imagine my surprise when I stumbled upon a way of thinking about logarithms that is so compelling and intuitive, it makes these rules completely obvious! Instead of having to stuff complicated algebraic expressions in your brain, it allows you to rediscover these expressions on the spot with only a little common sense. I'm sure it's not completely original, but since I've never seen it described before, I think it's worth going over here. So let's get into it!

We'll begin with the first logarithm rule you learn, namely that adding two logarithms with the same base multiplies their arguments:

$$\log_a{(b)} + \log_a{(c)} = \log_a{(bc)}$$

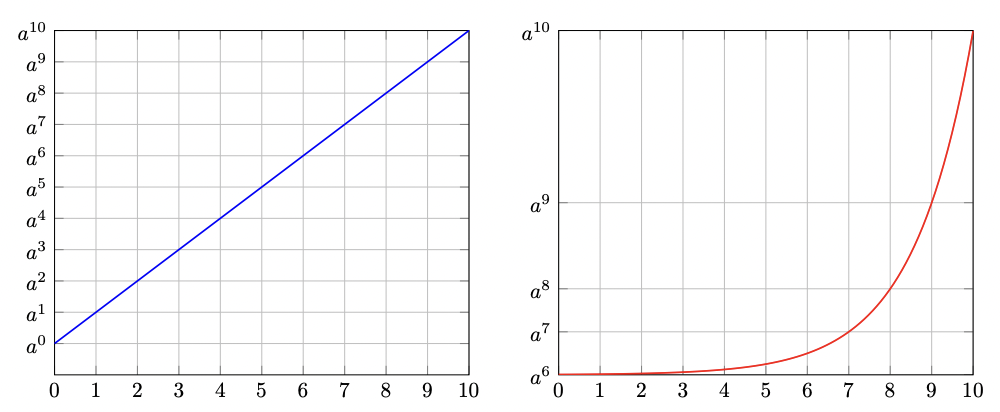

Why is this true? I could wave my hands about how this property is the mirror-opposite of the one for exponents (when they multiply, their arguments add), or even conjure up an \(x\) and \(y\) to prove it. But this still doesn't give us any intuition. To do this, we have to fundamentally rethink what a logarithm is. What I'm going to try and convince you is that a logarithm is nothing more than a stopwatch for an exponentially growing process – a glorified clock.

Consider the following example:

$$\log_2{(3)}$$

What does this expression mean? The typical answer is something like: the logarithm is the answer to the question two raised to what equals three? But I want you to think of the logarithm as asking a different question instead: how many units of time does a doubling process take to triple? Let's break that down a bit.

By “doubling process” I just mean something that multiplies itself by two after every whole unit of time, i.e., after one unit of time it's twice as much it was initially, after two units, it's four times as much, etc. It doesn't matter what exactly this process is, though I tend to think of it as a tower of blocks being stacked one after another.1

Now, I know what you're thinking: how exactly does transforming the question of logarithms from a mathematically precise one to one dealing with growing towers of blocks help us out at all? Like with most math, showing is better than telling. So let's put this idea to work. If we forgot the first rule of logarithmic arithmetic, but remembered this one insight, how might we simplify the following expression?

$$\log_2{(3)} + \log_2{(15)}$$

First, let's translate it into our new mental framework. Remember, \(\log_2{(3)}\) asks how long a doubling process takes to triple, while \(\log_2{(15)}\) asks how long a doubling process takes to 15-times itself. In other words, we set off our first process and record how long it takes to triple. If we think about these processes as stacks of blocks, then each stack starts out with one block, and tripling happens when we reach three blocks. Once the first process triples, we start the next one on a new block, and wait until it grows to a tower of fifteen blocks. The time it takes for both of these processes to finish is our answer.

Of course, you may wonder why we need two towers of blocks. That seems inconvenient. Why can't we just start our second tower – our second process – on top of our first? Well, there's actually nothing stopping us from doing so. Except now, the process will start with three blocks, so 15-timing itself looks like a tower with \(3 \times 15 = 45\) blocks. The time it takes to get from three to forty-five blocks is the same as it takes to get from one to fifteen – both processes grow at the same rate,2 but with different inputs.

And therein lies the beauty of this approach! We just discovered the first rule of logarithms through...common sense. Instead of asking how long it takes for one doubling process to triple plus how long it takes another to 15-times itself, we realized we can just ask how long it takes a doubling process to do both of these things, or 45-times itself. There's nothing to memorize or derive. By relying on our very intuitive, physically-grounded understanding of how things grow, this fact is now self-evident: adding logarithms multiplies their arguments.

And we can do the same for the other logarithm rules, too. For example, the rule for subtracting two logarithms with the same base tells us to divide their arguments:

$$\log_a{(b)} - \log_a{(c)} = \log_a{\left( \frac{b}{c} \right)}$$

Again, assuming we forgot this rule, how might we simplify the following expression?

$$\log_2{(15)} - \log_2{(3)}$$

Armed with our new understanding of logarithms, we know that all this expression is asking is the difference between how long it takes a doubling process to 15-times itself versus tripling. We can very cleanly picture this difference as the difference between the heights of our two towers – the one with fifteen blocks and the one with three. Since the two towers grow at the same rate, they're identical up until the point that they have three blocks. However, after that point, the first tower grows an additional twelve. So the time spent fleshing out this region of twelve blocks is the answer we're looking for. But how do we calculate it?

Well, we first need to switch from an additive point of view to a multiplicative one. In this region, the tower grows from three to fifteen blocks, so it grows by a factor of \(\frac{15}{3} = 5\), or quintuples. And, since the process continues to grow at the same rate as before, the time spent in that region is however long it takes a doubling process to quintuple, or \(\log_2{(5)}\).

Again, this makes total sense. Instead of asking how long it takes for one doubling process to 15-times itself minus how long it takes another to triple, we can just ask how long it takes for a doubling process to cover the difference between the two, or quintuple.

Now that we've got the hang of things, let's look at some more interesting rules, like:

$$\log_a{(b^n)} = n \log_a{b}$$

This rule says that the amount of time it takes an \(a\)-ing process to \(b\)-times itself \(n\) times is equal to \(n\) times however long it takes that same process to \(b\)-times itself once. To make things more concrete, imagine we had the example \(\log_2{(5^3)}\). This is just another way of saying \(\log_2{(5 \times 5 \times 5)}\) or, how long does it take a doubling process to quintuple three times? Since the process always takes the same amount of time to quintuple, this is obviously just three times however long it takes to quintuple once, or \(3 \cdot \log_2{(5)}\).

Following this same line of reasoning, we can see how:

$$\log_{(a^n)}{(b^n)} = \log_a{b}$$

For instance, imagine we had the logarithm \(\log_{(2^3)}{(5)}\). This just asks how long a process that doubles itself three times for every whole unit of time takes to quintuple. Since this process doubles three times faster than a normal doubling process, it will always take a third of the time a normal doubling process does to do anything. More generally:

$$\log_{a^n}{(b)} = \frac{1}{n} \cdot \log_a{(b)}$$

Combining this fact with the rule that allows us to move exponents outside of a logarithm, it's trivial to see that the exponents in \(\log_{(a^n)}{(b^n)}\) will cancel out, leaving just \(\log_a{(b)}\) behind.

Here's another logarithm rule, which, at first glance, looks completely wrong: $$\left(\log_a{b}\right)\left(\log_c{d}\right) = \left(\log_a{d}\right)\left(\log_c{b}\right)$$

How could switching the arguments of the two logarithms we are multiplying together still give us the same answer? It's obvious that \(2^5 \cdot 3^{10}\) and \(2^{10} \cdot 3^5\) aren't the same thing, so why would this be true of logarithms? No amount of reasoning about \(a\)-ing and \(c\)-ing processes makes this much clearer. But, if we change perspective and rearrange this rule as follows:

$$\frac{\log_a{(b)}}{\log_a{(d)}} = \frac{\log_c{(b)}}{\log_c{(d)}}$$

Things suddenly begin to make a lot more sense! Let's first think about what this form of the equation is saying. It's declaring that two ratios are equal to one other, namely the ratio of how long it takes an \(a\)-ing process to grow to two different heights, and the ratio of how long it takes a \(c\)-ing process to grow to those same two heights.

Imagine, for a minute, that instead of towers of blocks, each process is represented by a runner. So the first ratio would be how long it takes runner \(a\) to run \(b\) – which we'll pretend is the distance of a mile – versus \(d\) – a half-mile, in our example. No matter how fast \(a\) runs – or \(c\) runs, for that matter – this ratio will always be the same. Whether we travel at the speed of light or that of Hawking radiation, there will always be two half-miles in a mile. This relationship between distances – between amounts of growth – is a natural constant.

The idea of dividing two logarithms with the same base to obtain a dimensionless quantity relating two different amounts of growth is very powerful. And, through the lens of our runner example, it now has an intuitive meaning as well In fact, we can use it to unearth my favorite logarithm rule, usually called the “change of base” rule. By simply taking \(d = c\) we get the following:

$$\log_a{b} = \left(\log_a{c}\right)\left(\log_c{b}\right)$$

In this form, the rule goes by my preferred name: the chain rule of logarithms. The name elucidates that all this rule really says is that if you chain together two logarithms, where the argument of one is the base of the other, then this repeated – or chained – term cancels out. However, it's more likely you'll find this rule in it change of base form:

$$\log_c{(b)} = \frac{\log_a{(b)}}{\log_a{(c)}}$$

This form better stresses the idea that the equation allows you to convert a logarithm of one base into a quotient of logarithms with any other base. The reason why this is true is the same as the more general case – we are converting between two expressions that both represent the universal constant of growth between \(b\) and \(c\). There is a just a \(\log_c{(c)}\) term that has been canceled out in the denominator on the left-hand side.

And that's pretty much all you'll ever need to know about logarithms.3 While thinking about them as asking how long exponentially growing processes will take to do something isn't always helpful – sometimes you do just need to manipulate symbols – it should always be enough to rediscover these fundamental logarithm rules, and remind and convince yourself of why they're true. For me, that's a great win!

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Dr. Steven Strogatz for reading over a first draft of this post. Also, thanks to Grant Sanderson for some feedback on brevity, and encouraging me to include at least one image!Footnotes

1. This analogy obviously has some issues because blocks are discrete and exponential growth is not. However, instead of thinking of whole blocks being dropped one after another, you can think of them as being built up, bit by bit, which is more conducive to continuity. Really though, it doesn't matter, because we're not trying to be rigorous here, but rather give ourselves a tool to visualize with. ↩

2. I should clarify what I mean by “rate” here. Obviously, as it gets further along it in its growth, the exponential process that a given logarithm is modeling is going to grow more quickly. That is, after all, what exponential processes are supposed to do. However, if we take “rate” to mean the amount of time it takes for the logarithm's underlying exponential process to replicate itself (which for a doubling process means doubling, for a tripling process means tripling, etc.) then a process's rate does remain constant. ↩

3. I also love this identity and think it's worth knowing: \(\frac{1}{\log_a{(b)}} = \log_b{(a)}\). See if you can prove why it's true! ↩